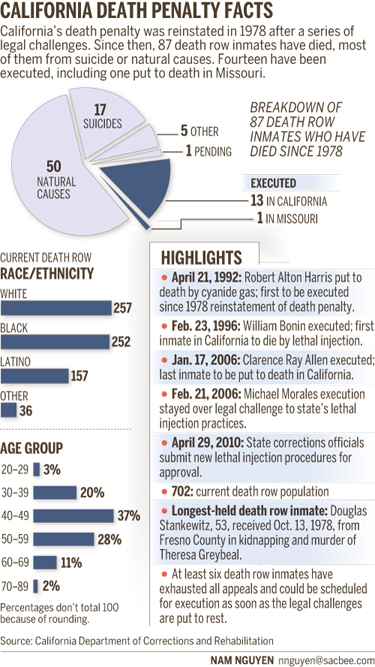

When Caryl Chessman died in California's gas chamber 50 years ago - probably the state's most notorious execution - 18 inmates were left on death row. Today, there are 702.

The last execution at San Quentin State Prison was that of Clarence Ray Allen on Jan. 17, 2006, the 13th in California since 1978.

Since that day, at least 205 convicts have been executed in other states, 24 death row inmates at San Quentin have died from natural causes or suicide, and 83 people have been sentenced to death in California courts.

But no one has been executed in California since Allen. That's largely because of two court challenges over the state's lethal injection methods and its attempt to short-circuit the procedure for revising those methods.

Now corrections officials hope they are on the verge of winning approval of their rewritten lethal injection rules, which will give the rules the force of law.

That approval, due by Friday, will reignite a pending legal battle over whether California can rejoin 34 other states that have the death penalty, and whether it should.

Supporters and opponents say the likelihood of executions resuming anytime soon in California is slight.

"I've just kind of lost faith in the system, that it's ever going to work," said Barbara Christian, a 72-year-old Wilton woman whose daughter, Terri Lynn Winchell, was savagely raped and murdered 29 years ago when she was 17. "I'd like to see justice for my daughter."

Central to issue

Winchell's murder is at the heart of the moratorium on the death penalty in California.

Michael Morales, who hit Winchell in the head at least 23 times with a hammer, dragged her into a field and raped her while she was unconscious and then plunged a knife into her chest four times, was scheduled to die Feb. 21, 2006, for the crimes.

But the two anesthesiologists who were to monitor the lethal injection under rules set down by a San Jose federal judge backed out at the last minute, and the Morales execution was stayed.

Subsequently, legal challenges played out in two different courts. Corrections officials rewrote the lethal injection procedures in a bid to satisfy U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel, who earlier had ruled that they posed a risk of cruel and unusual punishment and needed to be altered.

In November 2007, a Marin Superior Court judge barred the changes, saying they needed public review and approval by an obscure state agency. A hearing in Sacramento drew death penalty opponents from around the state and 102 speakers. The Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation was bombarded with 20,000 written comments.

The 42-page final rewrite of the procedures includes an elaborate process for selecting and training an execution team as well as tight controls and record-keeping on the storage and use of the three drugs meant to knock out inmates, then paralyze them and, finally, stop their hearts.

The duties of each team and sub-unit are spelled out in minute detail, starting well before the day of execution.

Meanwhile, the department constructed a new death chamber at San Quentin in an attempt to satisfy other concerns Fogel had.

The revised procedures were submitted for review April 29 to the state Office of Administrative Law. Its approval would likely resolve the Marin court's injunction.

But the constitutional challenge before Fogel is a much higher hurdle.

Constitutional questions

He concluded in December 2006 that the state's capital punishment methods were unconstitutional. He said the records of previous executions exposed "actions and failures to act" that created a risk of cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Constitution's Eighth Amendment.

"This is intolerable," he declared.

The first drug to be administered - sodium thiopental - is meant to anesthetize the inmate before two other drugs - pancuronium bromide, which paralyzes, and potassium chloride, which causes cardiac arrest - are administered.

One of the key arguments in California, and in several other lethal injection challenges around the country, is that the anesthetic has not been totally effective, resulting in extreme pain that the paralyzed inmate feels but cannot express.

During the next legal round in San Jose, Morales' lawyers are expected to argue the new rules still offer no guarantee that the three-drug protocol will not subject the inmate to excruciating pain.

The revised rules call for a correctional officer in the execution room to monitor the intravenous lines and "assess the consciousness of the inmate throughout the execution" by brushing the back of his/her hand over the inmate's eyelashes, speaking to and gently shaking the inmate. "If the inmate is unresponsive, it will demonstrate that the inmate is unconscious."

If, after two syringes of sodium thiopental and a saline flush, the officer's assessment is that the inmate is not unconscious, the entire sequence is to be re-initiated.

Opposing viewpoint

Natasha Minsker, death penalty policy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, is derisive of the proposed procedures.

"The governor and the Department of Corrections are simply tinkering with the machinery of death, and have not dealt with any fundamental problems," she said in a telephone interview.

"They have simply ignored the thousands of comments and are plowing ahead with the same stale approach," Minsker said. "The rules don't address the religious rights of inmates, the First Amendment right of the press to see the entire procedure, including a view of other witnesses. And the administration insists on employing the same paralytic that has been the culprit in countless bungled executions."

But Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, which favors the death penalty, said he believes the state will be in a much stronger position when it gets back before Fogel because of an intervening decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The high court upheld Kentucky's lethal injection method in a 2008 opinion that "is right on point," Scheidegger said in a telephone interview. "The argument there - that the three-drug cocktail poses a risk of unacceptable pain - was the same as the one in the Morales case, and the court has spoken on the issue. I don't know what more his lawyers can say.

"In fact, the protocol California had to begin with was better than the one they had in Kentucky, and now California has made it even more fail-safe."

No matter how Fogel rules, the Morales case will move on to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, perhaps before an expanded panel. And some observers say the U.S. Supreme Court may decide to accept it for review because of the massive amount of evidence accumulated in California.