When LAPD Public Information Director Mary Grady discusses the department's community-based counterterrorism initiative known as iWatch, she repeatedly refers to "suspicious activities and behaviors." That's a specific and intentional phrase, with "activities and behaviors" employed rather than "suspicious-looking people."

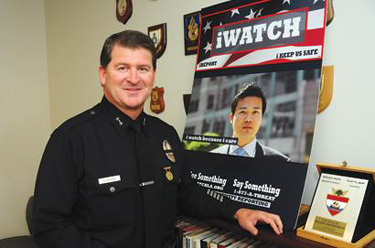

LAPD Deputy Chief Michael Downing leads the department's Counter-Terrorism and Criminal Intelligence Bureau. The iWatch program is an attempt to promote public involvement. (Photo by Gary Leonard)

The department announced iWatch, which asks the public to report activities that may be tied to terrorism, last October. Now, as officials continue to quietly roll out the program, the focus is on schooling people to recognize what kinds of behaviors are really dubious, and what kinds of suspicions amount to racial profiling.

It's an issue that commands special attention in Downtown Los Angeles, where the cluster of government offices, sports and entertainment centers and high-rises, including the tallest building west of the Mississippi, make potential high-profile targets. The matter takes on even more urgency in the wake of the failed bombing last week in Times Square.

In the years following the Sept. 11 attacks, said LAPD Deputy Chief Michael Downing, who heads the Counter-Terrorism and Criminal Intelligence Bureau, "We would get these reports that I would call MWC - Muslim With Cameras - and that's not against the law. It's not suspicious. Somebody can wear a burka and take pictures and there's no reason to be alarmed."

iWatch is really the second phase of a counterterrorism strategy that began in April 2008 under former Chief William Bratton. With the internal implementation of SAR, or Suspicious Activity Reporting, the department identified some 65 acts, from surveillance to trespassing, and trained officers to look for and report those incidents.

When it came to devising iWatch, the department turned largely to volunteer reserve specialist Rene Greif, an attorney who became interested in counterterrorism in the post 9/11 era.

"I think some people think that this is law enforcement's job whether it's local or state or at the federal level, and that people shouldn't be involved in this," Greif said. "For me, I look at it as completely the opposite. I think that we are a part of the solution. We can help and I don't see why we shouldn't."

Public Presentation

With the SAR system now firmly integrated within the department, Grady and her team, including Greif, are leading a push to roll iWatch out to the public. They're presenting the program at community police advisory board sessions, meeting with major employers in the city, and are sharing the plan with local media outlets in the effort to help spread the word. This month, Los Angeles World Airports is slated to put up posters and distribute literature on the program at LAX.

Grady notes that getting the public to keep an eye open for suspicious activity is nothing new. On a localized level, such behavior forms the basis for many neighborhood watch groups. The difference here is the effort to train citizens to be aware of things that, pre-iWatch, they might not have recognized as potential indicators of terrorism.

In a short film that the department features on its iWatch website (iwatchla.org) a detective pieces together some seemingly unconnected tips: a garden supplier notes a client's purchase of a large amount of fertilizer; a security guard observes a van casing a Downtown office tower and taking photos; a man smells diesel fumes coming from a neighbor's garage. The tips help uncover a plot to bomb critical city infrastructure. At least that's how the department hopes the program plays out.

Although the LAPD is hoping to draw community support, iWatch has already been met with some criticism. Last October, the American Civil Liberties Union expressed concern that the program will encourage the public to report suspicious activities that could just as well be innocuous.

Peter Bibring, an attorney with the Los Angeles chapter of the ACLU, pointed to some of the allegedly suspicious activities and behaviors outlined on the iWatch website. In a pamphlet geared toward shopping centers and malls, these include obvious red flags such as unusual inquiries about security procedures and unattended bags. But Bibring noted that it also warns against individuals with "unseasonal bulky attire."

"That's half the high school kids in Los Angeles, right?" said Bibring, who worries that some of the suspicious activity reporting invites racial and religious profiling. "The problem here is not that the department is open to taking citizen complaints. It's that they're engaging in this campaign to get people to report with only vaguely defined standards about what should be reported, and what it really amounts to is a call for people to react to their gut instinct, and it's peoples' gut instincts that are often informed by biases."

Downing dismisses the idea that iWatch prompts that response. In fact, it's his hope that it will encourage the opposite.

By focusing on behaviors and activities, Downing believes iWatch will start to steer the public toward an understanding that the threat of terrorism in America is not confined to radical Muslim plots.

"We can't be a one-eyed Cyclops in our approach," Downing said. "I think what we need to be able to do is convince the public, the American public really, that they have a responsibility to step up, that they have a stake in keeping a peaceful, resilient community for their kids.

"Just report it and then we'll decide what to do with it."