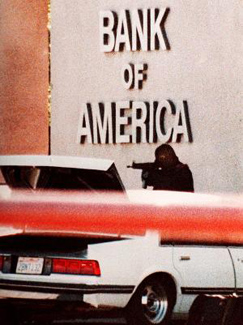

One of the bank robbers in the Feb. 28, 1997 North Hollywood shootout fires at officers and bystanders. (Gene Blevins/Los Angeles Daily News)

For the dozens of officers called to respond to the bank robbery in North Hollywood 15 years ago, it was like looking into the face of hell. | Police audio from that day

Video: Photographer Gene Blevins remembers

"They were demons, devils," LAPD Assistant Chief Michel Moore now recalls of Larry Phillips and Emil Matasareanu, who wore black ski masks, reinforced military-grade body armor and armed themselves with automatic weapons as they attempted their long-planned robbery of the Bank of America branch.

Moore, then a watch commander in LAPD's Wilshire Division, was one of the hundreds of officers summoned from throughout the city to the call of "Shots fired, bank robbery in progress" on Feb. 28, 1997.

When law enforcement descended on the scene, the heist-gone-bad turned into 44 minutes of gunfire as the robbers sprayed some 1,100 armor-piercing bullets at officers and nearby homes. More than 300 sworn personnel returned fire with 750 rounds -- all while news helicopters circled above, broadcasting the North Hollywood shootout for the nation to see.

"We had trained for terrorists as part of the Olympics, but this was beyond what anyone thought would ever happen," Moore said.

Fifteen years later, the day is still vivid in the minds of those who witnessed the shootout and it's become part of the cultural lore of Los Angeles.

The robbers' getaway car, the weapons and the body armor used are all on display at the Los Angeles Police Historical Society Museum.

"It is our most popular exhibit," director Glynn Martin said. "Maybe it's because it was so recent or the fact it was on television, but everyone wants to see it."

Matasareanu, 27, and Phillips, 31, were believed to have pulled off a number of earlier bank heists in the area. But the North Hollywood robbery was to be their biggest yet.

The bank was expected to have more than $750,000 in cash on hand to accommodate a Friday payday.

The pair, drawn together by a love of weight lifting and weapons, had planned for months -- assembling the body armor and reinforcing it over vital organs. They had obtained a number of weapons, including automatic rifles and had more than 3,300 rounds of ammunition, many of them armor-piercing bullets.

LAPD officers take cover in the Hughes Market parking lot during the Feb. 28, 1997 North Hollywood shootout. (Gene Blevins/Los Angeles Daily News)

On the morning of the robbery, officials said they believe the pair took some phenobarbitals to help control their nerves.

Shortly before 9:30 a.m., they pulled up to the bank at 6600 Laurel Canyon Blvd. and synchronized their watches to account for an anticipated eight-minute LAPD response time once they entered the bank.

But as the pair lumbered from their Chevrolet Celebrity sedan, they were spotted by LAPD Officers Loren Farrell and Martin Perello, who were on patrol and called in for backup for a possible robbery.

Inside the bank, the two gunmen shot out the tellers' windows and forced their way into the vault. In the time it took them to place the money on a cart and leave the building, the LAPD had surrounded the bank and the SWAT team was on its way.

Some SWAT members had been working out at the LAPD Academy and arrived in gym shorts and bullet-proof vests.

As quickly as the officers arrived, so did television helicopters and news crews to record the events.

Over the next 44 minutes -- which became a title of a movie about the events -- a nationwide television audience watched, transfixed as the robbers and officers faced off.

Councilman Dennis Zine, who was a motor officer at the time, also responded to the scene and said it was unlike anything he had experienced.

"All our training was that we would respond with extra force and we expect them to surrender," Zine said. "None of that happened."

Matasareanu and Phillips went off on foot in different directions after police shot out the tires on their car.

Phillips walked down Archwood Street, continuing his gunbattle with police until he was no longer able to advance and he shot himself.

Employees emerge from the Bank of America after the Feb. 28, 1997 North Hollywood shootout. (Gene Blevins/Los Angeles Daily News)

Matasareanu tried to hijack a pickup truck, but he was unable to get it started and then began a six-minute gunbattle with police, until he collapsed from his injuries.

Matasareanu died at the scene even though an ambulance had been called.

His family would later file suit against the LAPD, alleging officers allowed him to die. Stephen Yagman, the attorney who represented the family, said the jury deadlocked six to six.

Yagman said Matasareanu and Phillips were introduced to one another by members of the Montana Militia, which financed their criminal activities, providing them with the body armor and weapons in return for a share of the bank robbery proceeds.

Yagman said Matasareanu was suffering with a brain tumor for which he was unable to afford medical treatment.

"It was driving him crazy," Yagman said. "He and Phillips spent most of their time on speed balls and watching a movie about armored car robberies. On Feb. 28, 1997, the North Hollywood robbery was to be their latest.

"I always was amazed that given what went on out there that no one else was killed or even seriously hurt," Yagman said. "It was a semimiracle."

In the end, the two robbers were the only deaths. Eleven police officers were injured as were six civilians. Eventually, the department would award the Medal of Valor to 19 officers.

Still, the North Hollywood shootout highlighted how officers were unprepared to face off against heavily armed suspects. In the middle of the gunbattle, five officers went to the B&B Gun Shop, which has since closed down, and borrowed weapons and ammunition.

In the days and years after the shootout, the LAPD secured surplus M-16s from the U.S. Department of Defense. And state legislators passed a law that allowed peace officers to purchase assault weapons -- which were outlawed for civilians.

Some in the community still vividly remember the day and their role in the infamous shootout. Dr. Jorge Montes is a dentist who has a second-floor office across the street from the bank.

"I could re-enact it," Montes said, telling how he gestured to two police officers who were shot to make their way up to his office so he could help them.

Montes, relying on first aid courses he had taken, was able to stabilize the two officers who made their way to him even as bullets rained into the office building and Montes' van.

The day solidified his commitment to the neighborhood.

"I love this community, and I'm part of its history," Montes said. "I love my patients and I love this area."