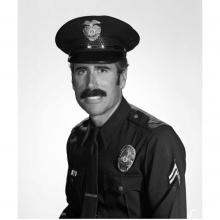

LOS ANGELES (AP) — On June 2, 1983, Los Angeles Police Officer Paul Verna was killed in the line of duty.

That is not in dispute.

What is, however, is who pulled the trigger. And a combination of factors — from the current political climate to anti-police sentiments gripping the nation to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s race next month — could impact what happens next.

For the Verna family, it means the man prosecutors say fired five bullets into the officer 37 years ago could go free.

“When’s it going to stop?” Verna’s oldest son Bryce said this week. “When’s it over? When is justice going to be served?”

On June 2, 1983, during a traffic stop in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, authorities say Raynard Cummings fired one bullet into Verna’s body and Kenneth Earl Gay fired five more. Both pointed to the other as the shooter and both were sentenced to death.

The California Supreme Court has twice overturned Gay’s death penalty sentence and in February vacated his original conviction. The Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office must decide by Dec. 14 if prosecutors will re-file the case.

“If we don’t prosecute people who hurt and kill police officers, we’ve got an issue in society,” Verna’s youngest son Ryan said.

Gay, now 62, remains incarcerated in San Quentin State Prison. He maintains his innocence.

There is a court hearing Friday on the defense’s motion to dismiss the case. The LA public defender’s office, which is currently representing Gay, did not return requests for comment.

A spokesman for the district attorney said officials are still reviewing the evidence. The current district attorney, Jackie Lacey, is facing a tough reelection and her opponent is against the death penalty.

On June 2, 1983, Verna was 35. He had been an Eagle Scout, an Air Force veteran and a member of the Los Angeles Fire Department for 364 days.

A jokester with a love for baseball — he rooted for the then-California Angels and coached Little League — he met his wife Sandy on a blind date. He adored animals and loved feeding them at the zoo, pointedly ignoring all the signs prohibiting exactly that.

His sons, Bryce and Ryan, barely remember any of it.

On June 2, 1983, Gay and his co-defendant, Cummings, were passengers in a car that Verna, a motorcycle officer, stopped for speeding through a stop sign in Lake View Terrace, a suburban neighborhood in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley.

Prosecutors said the two men, who had committed more than a dozen robberies in the weeks before the shooting, thought Verna would arrest them because they were armed ex-convicts riding in a stolen car.

Verna wrote down Pamela Cummings’ name — a crucial move that later helped detectives solve the murder — and leaned into the car to ask Cummings and Gay for identification. Cummings fired the first shot and then, prosecutors say, passed the gun to Gay, who jumped out of the car to pump another five bullets into the officer.

On June 2, 1983, Verna’s family was home. Bryce was 9 years old, his brother a few months shy of 5. His wife, now Sandy Jackson, was cooking dinner when the first police cars arrived to rush her to the emergency room. She told her children the tragic news the next day.

“Ryan just wanted his blankie, he wanted his favorite animal and he just wanted his daddy,” Jackson said. “That was, to me, the most heartbreaking, heart-wrenching thing to live through. Having my kids want their daddy — and not being able to give them that.”

Now, 46-year-old Bryce is a motorcycle officer with the LAPD and wears a badge with his father’s number. Ryan, 42, is a retired homicide detective who looks just like his dad.

Both men are frustrated by the decades of delays and wonder if Cummings and Gay will ever be executed. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order last year placing a moratorium on the death penalty.

The original trial was held in 1985 and separate juries convicted Cummings and Gay, who each accused the other of being the shooter, and recommended the death penalty. Three years later, the state Supreme Court overturned Gay’s death sentence on the grounds of incompetent counsel, but left the guilty verdict in place.

The court again sentenced Gay to death in 2000 after a retrial just for the penalty phase of the case. The high court overturned that, too, and in February, the justices unanimously decided to vacate Gay’s initial guilty conviction. The justices wrote that Gay’s attorney, Daye Shinn — who was later disbarred and has since died — among other things, did not introduce crucial evidence that might have swayed the jury to come to a different verdict.

Gay has apologized to the Verna family for the pain that insisting his innocence has caused them.

“Mrs. Verna, for what it is worth, I extend my sincere and heartfelt condolences to you and your family, but I didn’t kill the guy,” he said in court in 1985.

Cummings remains on death row in San Quentin.

Therene Powell, a retired state public defender who represented Gay in his second appeal of the death penalty, said several witnesses described what Cummings looked like even as they said it was Gay who fired the final shots, while others said he was not involved in the shooting.

“There was a great deal of evidence in his favor that should have been presented and was not,” Powell said. “It is definitely more likely than not that he is innocent of the murder charges.”

While on death row, Gay wrote a screenplay, “A Children’s Story,” which won an American Film Institute contest in 1994.

The Verna family continues to press prosecutors to re-try the case. Ryan said “37 years of games and technicalities” has shaken his faith in the justice system.

It’s possible the case might not be re-filed, or the jurors might not find Gay guilty again — a stronger likelihood in the current political climate than in the 1980s. Gay could be released from prison in a matter of months.

“I really have trouble wrapping my head around that,” Jackson said.

More than 700 people have written letters to the office in support of the Vernas and dozens of officers are expected to be in court Friday.

“You have to honor the family, because they’re all victims,” said Craig Lally, president of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union that represents rank-and-file officers. “These people that kill cops should never be able to walk the face of the earth again.”

LAPD Chief Michel Moore briefly worked as Verna’s partner and said the officer excelled at defusing tense situations — a tactic now called de-escalation — with his “calm demeanor and soft heart.”

“We can never bring Paul back with this justice,” Moore said. “But we can send a message to the family and every law enforcement officer that the death of a police officer at the hands of another, that the brutal assault, the senselessness of this killing — time doesn’t lessen or remove that severity.”

On Oct. 6, Verna would have turned 73. He might have spent his birthday with Bryce riding motorcycles, playing with Ryan’s kids or driving up to the California coast with Jackson like they did on their first date.

Instead, he’s buried in a Chatsworth cemetery, in a picturesque place in the San Fernando Valley near a big oak tree.

On June 2 of every year, Bryce, Ryan and Jackson visit his grave.

“I’m trying to do everything that I can do so that if he has a chance to look down right now,” Ryan said, “he’s seeing that his family is fighting for him.”