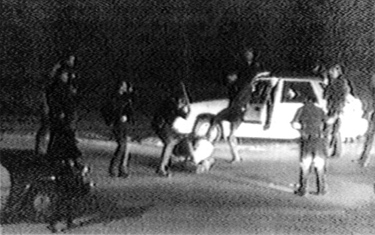

The nine minutes of grainy video footage George Holliday captured of Los Angeles police beating Rodney King 20 years ago helped to spur dramatic reforms in a department that many felt operated with impunity. (George Holliday)

It was shortly after midnight, 20 years ago Thursday, when George Holliday awoke to the sounds of police sirens outside his Lake View Terrace apartment. Grabbing his clunky Sony Handycam, he stepped out on his balcony and changed the Los Angeles Police Department forever.

The nine minutes of grainy video footage he captured of Los Angeles police beating Rodney King helped to spur dramatic reforms in a department that many felt operated with impunity. The video played a central role in the criminal trial of four officers, whose not-guilty verdicts in 1992 triggered days of rioting in Los Angeles in which more than 50 people died.

The simple existence of the video was something unusual in itself. Relatively few people then had video cameras, Holliday did - and had the wherewithal to turn it on.

"It was just coincidence," Holliday reflected in an interview a decade ago. "Or luck."

Today, things are far different and the tape that so tainted the LAPD has a clear legacy in how officers think about their jobs. Police now work in a YouTube world in which cellphones double as cameras, news helicopters transmit close-up footage of unfolding police pursuits, and surveillance cameras capture arrests or shootings. Police officials are increasingly recording their officers. Compared to the cops who beat King, officers these days hit the streets with a new reality ingrained in their minds: Someone is always watching.

"Early on in their training, I always tell them, 'I don't care if you're in a bathroom taking care of your personal business.... Whatever you do, assume it will be caught on video,' " said Sgt. Heather Fungaroli, who supervises recruits at the LAPD's academy. "We tell them if they're doing the right thing then they have no reason to worry."

The ubiquitous use of cameras by the public has helped serve as a deterrent to police abuse, said Geoff Alpert, a leading expert on police misconduct.

"At the time of King it was just fortuitous that someone had a camera," Alpert said. "Things are a whole lot more transparent now and if you're going to do something stupid, then you're going to pay for your stupidity."

Although some officers remain uncomfortable about people filming them, the culture shift has been particularly profound among younger officers who grew up in a world of mobile video and picture-sharing.

"We grew up with reality TV and smart phones. Everybody's life was on camera," said Joseph Stevens, a 26-year-old officer in the LAPD's West Bureau. "It's a given that everything I do could end up on television or YouTube. With the older era, they're still surprised at some of the technology.... They have questions about it but are starting to adapt."

Several recent cases show the power of questionable officer behavior going viral on the Web.

The use of cameras by the LAPD has evolved considerably over the years. Putting cameras in patrol cars was a key reform proposed by the Christopher Commission, which studied the LAPD after the King beating. After years of delays, the department recently installed cameras in a quarter of its cars and plans to outfit the rest of its fleet in coming years. In addition to deterring misconduct, police officials believe that cameras can help exonerate officers from false accusations.

The LAPD also sends its own photographers and videographers out to record large street protests or other incidents that could get out of hand. During training scenarios, drill instructors at the academy present recruits with various situations in which they must respond to the presence of cameras.

Some officers still bristle at the notion of a bystander recording them. In June, an LAPD officer confronted and then detained a man, who refused his orders to stop taping a traffic stop. Others accept the reality of ever-present cameras but worry that bystander videos can show a distorted version of an incident, particularly in the eyes of an uninformed viewer.

To "someone who doesn't understand police tactics or why we use force," an arrest of a violent suspect or similar situation can appear unnecessarily brutal, said LAPD Sgt. Alex Vargas, a veteran anti-gang supervisor in South Los Angeles. Routinely, he said, on-lookers begin filming only when officers are compelled to use force, "but you don't see [the suspect] attacking the officers. That's common."