Milton Conley's mental illness has cost him - and society - more than he cares to tally.

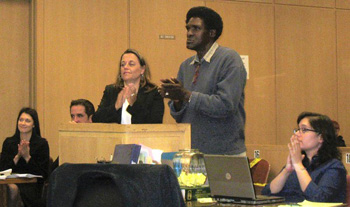

Deputy Public Defender Jennifer Johnson and Milton Conley stand at the podium in Judge Garrett Wong's courtroom, where Conley was applauded for following his treatment plan and believing in himself. (Lee Romney, Los Angeles Times / October 24, 2010)

An abusive father recruited Conley at age 9 into a life of what he calls "doing wrong things." A psychotic break in his 30s was followed by homelessness and four imprisonments, products of schizophrenia; addiction to crack cocaine and marijuana; and what Conley dolefully labels "being lonely."

The cycle is familiar: arrest, incarceration, release, descent into illness, re-arrest. But these days, Conley - earnest, with a flirtatious gleam and a tidy 1970s-style Afro - is living in a treatment program for substance abusers, meeting often with his caseworker and taking psychiatric medication.

The shift, hard and long in the making, comes thanks to San Francisco County's Behavioral Health Court, where a judge doles out weekly encouragement with occasional tough talk to keep clients engaged in comprehensive treatment.

"It's been a terrible life, but it's getting better, as long as I stay off drugs and alcohol and take my medication," Conley said recently as he waited for his weekly courtroom check-in.

About a fourth of California's jail and prison inmates are diagnosed with serious mental illness, according to a recent draft report by the Judicial Council's Task Force for Criminal Justice Collaboration on Mental Health Issues. Probationers are nearly twice as likely to reoffend if they are mentally ill, the report says, and mentally ill parolees are 36% more likely to violate their terms of release.

Given those realities, mental health courts are gaining credibility for their measureable successes.

In the normally staid courtroom, group applause rings out often, along with San Francisco Superior Court Judge Garrett Wong's pervasive "Good for you!" A deputy public defender and deputy district attorney work toward the same goals in a rare convergence. Mental health caseworkers facilitate housing, vocational training, counseling and other help for as many as 140 clients.

Participation is voluntary and comes in lieu of incarceration. The crime must be linked to the client's mental illness. Success can wipe charges off the books. Those who stumble seriously or often are removed from the program and re-jailed.

Today, there are 41 collaborative mental health courts in 29 California counties, up from 21 courts four years ago, according to the Judicial Council's Administrative Office of the Courts. Among the council task force's draft recommendations: that each county adopt a comparable approach that fits its needs.

Results are strong. A study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry this month examined San Francisco's court and three others nationwide and found "consistent evidence" that they are good for public safety, said Hank Steadman, the study's lead author.

Of those examined, San Francisco's court served the highest proportion of participants with schizophrenia and the greatest percentage who committed crimes against people rather than property. Yet San Francisco's program showed the greatest drop among the four courts in re-arrests compared to control groups, a 39% reduction compared to a 7% drop.

The control group also returned to incarceration for significantly longer periods than the mental health court participants.

Jennifer Johnson, a San Francisco deputy public defender who has helped craft the 8-year-old court, takes pride in the data and notes that "a program can't say it is protecting public safety unless it is directly addressing violence. That means accepting clients that actually put the community at risk."

San Francisco Dist. Atty. Kamala Harris said her office has objected to the participation of certain serious offenders. But Harris, who is running for California attorney general, said: "When you look at the numbers, you see that it actually makes sense, because we are reducing crime in the community."

About three years ago, Los Angeles County launched a similar court for those with multiple disorders of substance abuse and mental illness that can serve 54 people, said Alisa Dunn, who heads the county's Mental Health Court Linkage Program.

Dunn also oversees a program launched in 1987 that sends caseworkers into 25 courts from Long Beach to Pomona to counsel families and ensure that mentally ill defendants are plugged into an array of services, both in jail and upon release.

Although it is not a traditional behavioral court model - it does not promise diversion from jail nor does it always offer the chance of reduced or waived charges - Dunn said it works well for such a vast county. Last year, it served more than 2,600 people.

Through another program, Dunn's staff can now recommend that mentally ill inmates be diverted to a locked treatment facility of 46 beds or an unlocked alternative with 17, where they get intensive case management and care.

Collaborative mental health courts grew out of a similar model for drug offenders and were pioneered in California 11 years ago by Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Stephen Manley, whose court was also part of Steadman's study.

His court sees 1,700 clients with multiple disorders. It also serves mentally ill parole violators in a pilot program that will roll out this month in seven more counties, including Los Angeles and San Francisco.

"We are either going to take responsibility and try to get these people engaged in treatment," Manley said, "or we are just going to see them come through again and again - forever."

But the Judge David L. Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, based in Washington, D.C., considers behavioral health courts a late-stage intervention that can trigger unforeseen consequences when arrest is the only ready avenue to mental health treatment. The center would prefer to see resources spent on community mental health treatment that could engage people before arrest, said senior staff attorney Lewis Bossing.

Those who have sat on the judge's bench and witnessed lives changing, however, are true believers.

Superior Court Judge Mary Morgan shaped San Francisco's program before Wong took over in July. She called the intimate approach "head and shoulders above anything else that we do" for significantly increasing the likelihood that participants will stay in treatment longer and decreasing the likelihood that they will commit violent crime.

Imperfection is part of the process. Conley had done time at San Quentin after going through the program once. Then he reoffended. In 2008, while high on crack cocaine and off his meds, he said, he stole money from a street performer's tip cup. He was re-admitted.

But he stumbled and was jailed yet again when he took a $10 bill that was hanging from the pocket of an undercover officer posing as a passed-out homeless person.

Harris' office opposed his re-admission. But Conley was facing release to the streets on probation and posed a greater risk unsupervised, Johnson said. She and Conley's caseworker appealed to Morgan to give him another chance.

Today, Conley is off drugs and alcohol and stable on Haldol and other medications. If he goes off, he said, "I'm not Milton no more.... I can lose control of my life." He will receive training this month for In Our Own Voice, a program through which he will share the story of his schizophrenia with others like him.

"I want to give back," he said. "If one person can listen to what I have to say, I will have done my best."

A week after his successful court visit, Conley relapsed with street drugs, ending a long stretch of sobriety. But he visited his case worker, recounted his fall and expressed a strong desire to stay clean. Booted from his sober living housing, he stayed in a hotel while honoring his court appearances.

Last Thursday, the judge dispatched Conley straight to his parole agent, who found him new accommodations, complete with drug treatment services.

"Eventually, all of these people are not going to be in this program anymore," Johnson said.

"If they've learned how to deal with relapse and come through it, then they won't end up back in the criminal justice system.... This is hard, but in a strange way this is actually progress."