A program that Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca championed three years ago to sharply reduce the early release of jail inmates by placing as many as 2,000 additional offenders on electronic monitoring at home has failed to make a significant dent in the problem.

When he first announced the initiative in 2007 and prodded the state Legislature to allow it, Baca touted it as a major step that would free jail space and allow the department to keep more-serious offenders behind bars longer.

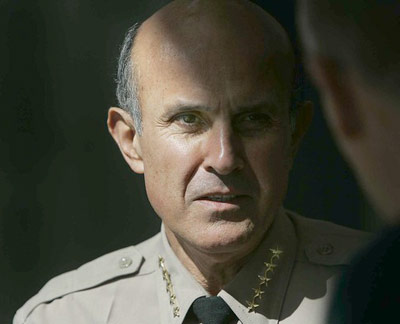

Before 2007, Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca could put inmates on home detention with electronic monitoring only if they volunteered for the program. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times / May 3, 2006)

But officials now concede the plan was based on a misunderstanding of the jail population. That doomed it from the outset.

Last week, only 135 inmates were involuntarily serving sentences at home, where they wear electronic ankle bracelets to track their movements, according to Sheriff's Department numbers provided to The Times.

There are now fewer inmates on home detention than when Baca pushed to expand the program in 2007, according to the records.

When they calculated how many inmates might be eligible for the program, sheriff's officials thought large numbers of nonviolent, low-security inmates suitable for home detention were in the jails. But their calculation took into account only the current charges inmates were being held on, officials concede. Once they reviewed the criminal histories of inmates, officials said they found many had serious or violent records that made them ineligible for home detention. "The myth of the low-security, nonviolent offender in jail is just that: a myth," said sheriff's spokesman Steve Whitmore

The failure of the program to live up to Baca's predictions underscores the sheriff's struggles to address one of the most vexing problems for L.A. County's criminal justice system over the last two decades: the early release of jail inmates. A 2006 Times investigation found that nearly 16,000 inmates released early were rearrested while they were supposed to be in jail. Sixteen were charged with murder.

Baca said the electronic monitoring program would ease overcrowding and decrease the number of early releases. But three weeks ago, faced with a new round of budget cuts, the sheriff announced that he was stepping up the early release. Inmates sentenced for nonviolent crimes, who used to serve at least 80% of their sentences, are now serving only about 50%.

Before 2007, Baca could put inmates on home detention with electronic monitoring only if they volunteered for the program. But as the jails released inmates early, sheriff's officials complained that most preferred to do their time in jail and leave after serving a fraction of their sentences without any supervision rather than serve their full sentences on home detention.

State Sen. Gloria Romero (D-Los Angeles), who carried the legislation, said she was surprised to learn it had made so little difference and suggested the sheriff review whether he could safely expand the program to other inmates in the jails.

"It really is a disappointment, especially given the massive overcrowding and the budget crisis," she said.

In an interview, Baca played down the results of home detention, saying other factors, such as court delays for inmates awaiting trial, have a more profound effect on jail overcrowding and early release.

Nevertheless, he said he would explore adding inmates to the program if they do not qualify under the county's current criteria but would otherwise be released early with no supervision. The county's rules are more restrictive than state law in terms of who can be released on electronic monitoring.

"Releasing people without accountability is a free ride," Baca said.

The department is planning to propose legislation that would allow Baca to put inmates awaiting trial on home detention if they are charged with nonviolent, non-serious crimes and have no history of violence. That would add an estimated 200 to 250 offenders to the program, officials said.

Sheriff's officials insisted that jail overcrowding has improved in recent years. The number of bookings has dipped, Whitmore said, and the state has become faster at picking up and transporting inmates who are sentenced to prison, reducing the county's jail population to about 16,500. Inmates serve more time today than they did four years ago, when tens of thousands did 10% of their sentences or less.

The American Civil Liberties Union has long called on the county to reduce the number of people who spend time in the nation's largest jail system. Peter J. Eliasberg, managing attorney for the ACLU of Southern California, which monitors conditions in the jails, said moving inmates to drug diversion, mental health treatment and electronic monitoring programs outside of the jails could improve conditions behind bars without threatening public safety.

After the law was changed to allow Baca to expand electronic monitoring, the sheriff's program was dogged by delays and missteps.

The county took more than 16 months to approve a contract with a company to oversee inmates on home detention, according to records. And sheriff's officials have failed to comply with a legal requirement to tell the state Corrections Standards Authority the names and offenses of all inmates on home detention and whether any were returned to jail while on the program.

Whitmore said jail managers mistakenly believed they were not required to make the reports. He said the department would immediately begin notifying the state about the electronic monitoring program.

In 2007, when the new law took effect, 413 offenders were on voluntary home detention. Last week, 394 were under voluntary or involuntary home detention.

Lt. Kevin Kuykendall, who oversees the program at the downtown Inmate Reception Center, said deputies have struggled to find the sort of inmates suitable for release because the jail's population is increasingly made up of offenders with lengthy criminal records.

"We were really gung-ho about getting it done and clearing people out," Kuykendall said. "These inmates just aren't qualifying."