The phone rang around 2 a.m., waking Teeida Townsend. "My homie got killed," the caller said.

Townsend knew how the cycle plays out here in the gang heartland of south Los Angeles: a killing, a revenge shooting, and then another. He rushed to the crime scene. Gang members were growing agitated. Beyond the yellow police tape, the bullet-riddled body of their teenage homeboy lay beneath a white sheet.

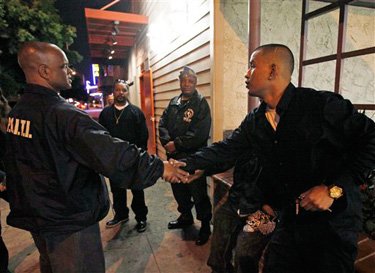

In this photo taken Feb. 26, 2010, Aquil Basheer, left, of the Professional Community Intervention Training Institute greets a pedestrian, as he gives a tour, outside the The Cottage bar where one of his intervention workers, Ronnie "Looney" Barron, was killed in a drive-by shooting on Feb. 7, 2010, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon)|

"'We have to keep calm, we don't want no retaliation, don't pick up those guns'," he remembered telling them.

Townsend's no cop. He's an ex-Crip, and one of the ranks of former gang bangers known as "gang interventionists" who police have come to rely on to ease tensions. But the recent felony convictions of several of them and the case of another accused of ordering a hit on a detective have undermined their credibility and proven an embarrassment to the city's anti-gang office that has funded them.

To bolster the program, officials are offering them training to help them walk the hazardous line between gangs and the police, without endangering themselves or others and without falling back into gang life.

"It's very difficult work to do and it takes a toll on the person," said Guillermo Cespedes, director of the Mayor's Office on Gang Reduction and Youth Development. "How to train professionals in that field is a challenge."

As ex-gang members, Townsend and his colleagues have singular access to a culture largely impenetrable to outsiders. With street credibility earned through gang exploits, doing prison time and even doing favors for gang leaders, gang code dictates these veterans are respected and have a "license to operate," or permission to move freely on gang turf.

But they must also make it clear to authorities and gang members that they no longer condone the gang life or participate in it. They can't however preach against the gang, which would alienate members.

At the same time, it can be a struggle for them to remain on the fringe of a life they swore allegiance to as teens, in some cases carrying on as a family tradition. It was a lifestyle they attested their loyalty to with tattoos, and gave them a sense of identity and community, as well as income from crime.

"The street has a hell of a pull," said 55-year-old Aquil Basheer, who runs the interventionist training course Professional Community Intervention Training Institute in South Los Angeles. "That's one of the biggest obstacles we face in this work."

City officials say it's worth taking a chance on ex-gang bangers because intervention can be uniquely effective in tamping down gang-related violence.

When an interventionist, Ronald Barron, was shot to death in February by a graffiti tagger he confronted, interventionists were called on to spread the word the killing was not gang-related, thwarting possible retaliation. When gangs held parties in parks known as "Hood Days," they negotiated with rival gangs to prevent gun-toting gatecrashers.

"I can't talk to the people you talk to," Los Angeles police Sgt. Curtis Woodle told Basheer's class. "We got to team up."

When Townsend arrived at the shooting scene on a recent Sunday morning, he set to work pacifying emotional gang members, while a colleague tried to console the victim's distraught relatives.

"They listened to me because they respect me as an O.G.," recalled the 46-year-old Townsend, referring to the term "original gangster" which means a longtime, well respected gang member.

"If you don't have no respect, these guys will laugh in your face," he said.

Dealing with armed, volatile gangsters can be dangerous work. Basheer recalled being threatened with a gun several times on the streets. "You got nothing but your own wit, personality and relationships in situations where all hell is breaking loose," he said.

Interventionists walk a particularly thin tight-rope when they interact with police. Gang members may think they are turncoats, and cops may believe they're still in the gang. They have to clarify they do not work as informants, and emphasize their focus is community safety, especially protection of children, and even individual gang members.

"It's a very, very hard line sometimes," said interventionist Leon Bryant, recalling one instance when he had to quickly allay gang members' suspicions when a cop approached him as he was talking to them.

Later, he had to tell the officer not to approach him so openly.

For many one-time gang members, families are a powerful motive to stay out of "the life."

Former homegirl Nicola Daugherty said she brought up three of her seven children to follow her footsteps. After serving prison time for selling cocaine, witnessing driveby shootings, seeing her 18-year-old brother killed, and finally changing her life through a church, she's now set on saving her own kids and others.

"I only taught my boys what I knew - gang-banging," the 40-year-old hairdresser said. "It's my duty and job to pull them out. It's still not too late."

The most successful gang interventionist is one who has made a deep personal commitment like Daugherty, experts say. But it's not always easy to immediately distinguish them. Many apply to courses after hearing about them through the grapevine.

A 37-year intervention veteran, Basheer carefully screens applicants for each class, looking at whether they have left the gang mentally, as well as physically. He tests them to see if they can work with rival gang members, wear colors associated with another gang, and cooperate with cops, for instance.

Lawyer Connie Rice, who oversees the city's contracted interventionist course, said she also looks for a spiritual transformation. "They've had an epiphany of some kind, often religious," she said.

After the courses, some interventionists are employed by nonprofit agencies under contract to the city, and others by nonprofits working independently. Salaries average about $36,000 a year. Many do the work informally as volunteers.

For Townsend, receiving letters from imprisoned former homeboys and the eyes of his five children and two grandchildren are a constant reminder not to fall back. He joined the gang at 13, and quit at 38.

"The temptation is always going to be there," he said. "But I never wanted to backslide. I've moved totally forward. God gave me a second chance. I'm trying to save some lives."