State parole officials are scaling back oversight for thousands of felons, bumping them to supervision levels that require nothing more than mail-in forms - or even a new level that includes no formal supervision at all.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation officials say they reduce oversight only for nonviolent and low-risk criminals as the agency pushes forward with an overhaul.

"There is no policy direction to the field to systematically reduce supervision levels," said Scott Kernan, the corrections undersecretary who oversees parole. "We have to manage our caseloads. We cannot have parole agents having artificially high caseloads."

But interviews, data and internal documents collected by The San Diego Union-Tribune over two months point to a methodical effort to cut costs and ease prison overcrowding. Fewer parolees, on lower supervision, mean fewer tickets back to prison for criminals who won't fit there.

"They don't want parolees back before the parole board to be returned to prison," said Harriet Salarno of Crime Victims United, an advocacy group suing the department over its release policies. "This is all about reducing the prison population."

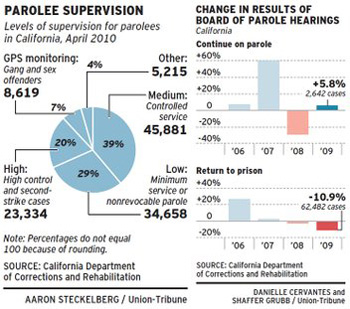

The department's numbers reflect the trend. Between April 2007 and April 2010, the parolee population fell about 10 percent overall. The number on "high control" supervision fell 13 percent, and the medium supervision level fell 22 percent. But the lowest supervision level grew 16 percent.

The prison system has come under increased scrutiny since convicted sex offender John Albert Gardner III was paroled and then went on to kill Amber Dubois, 14, of Escondido and Chelsea King, 17, of Poway.

Apart from Gardner's, the newspaper reviewed dozens of cases where serious and violent offenders were assigned low or infrequent supervision, only to commit new assaults, robberies or murders.

'Need to reclassify'

Early last year, a state parole administrator congratulated his Los Angeles staff for easing agent caseloads, including downgrading five high-control criminals so they had to see an agent only once every two months.

"I wanted to point out that your supervisors reduced more than 130 cases in your district," then-deputy parole director Robert Ambroselli wrote. "Please convey our sincere appreciation to your supervisors for their very hard work and their willingness to get things done. GREAT JOB!!!"

The e-mail was forwarded to supervisors by Vincent Thompson, then a district administrator.

"Review the e-mail from Mr. Ambroselli," he wrote. "You need to reclassify cases to bring relief to the agents in the district."

Relief in the form of new parole agents is slow to come amid the state budget crisis. So the state manages agent caseloads by weighing parolees on a point scale. Lower supervision levels are assigned lower points, allowing agents to take on more cases.

Corrections officials deny that Ambroselli's memo about "workload point reduction statistics" shows an effort to reduce supervision levels. They say it had to do with routine case reviews to make sure parolees were monitored at the correct level - whether lower or higher.

Ambroselli said the e-mail was not his only communication with the staff.

"I told them specifically, 'This is not an attempt to get somebody to lower points just to lower points,' " he said.

But internal records show that controlling expenses by reducing parolee supervision levels has been a consideration of top Division of Adult Parole Operations officials for years.

Regional administrator Mark Epstein wrote to his Los Angeles subordinates in 2005 about agent overtime and other implications of failing to move parolees to lower supervision levels. For instance, at the minimum supervision or MS level, parolees mail in a monthly form, with no requirement to see their parole agent.

"These numbers are disturbing for a number of reasons," Epstein wrote. "Units with MS levels below the regional or divisional averages may be contributing to excessive workload/points."

The memo spells out optimal workloads, including a guideline that no more than 15 percent of parolees be on the top supervision level.

"That's a fair percentage," Ambroselli said, discussing the goals set in the memo. "It's like a gas gauge - when it gets to a quarter-tank, you should begin to look for fuel for your vehicle."

A year ago, the state agreed to pay $900,000 to settle a lawsuit filed by former parole supervisor Rebecca Hernandez. She claimed she was discriminated against because of her unwillingness to keep down overtime by lowering supervision to levels that would be dangerous for the community.

"They made it a competition between supervisors," said Hernandez, who retired in January as a supervisor in Huntington Park. "They wanted 29 percent of the cases on minimum supervision. They told me, 'You're only at 9 percent. You need to work harder to get people on mail-in status.' "

At the time Ambroselli wrote the congratulatory memo to the Los Angeles staff, he was deputy director of state parole. Since then, he has been promoted to director of the division. He also was given a significant raise that pushed his salary to just under $150,000.

Including the new category of unsupervised parole, the department now has 29 percent of its parolees on minimal supervision, up from 21 percent in 2007.

New crime victims

Less supervision of parolees can translate to more crimes and more victims, department records indicate.

The Union-Tribune obtained hundreds of pages of parole documents, including dozens of daily reports that summarize parolee crimes committed the prior day. The daily briefings offer accounts of homicides, rapes, assaults and parolees fleeing police.

The reports include "face sheets" of parolees listing their supervision status at the time of the incident. Although the reports do not indicate previous supervision levels, retired agents say these kinds of cases indicate mistakes in classification - probably brought on by pressure to have lower caseload points.

"In an attempt to reduce costs, they are reducing parole classifications so agents don't have to provide supervision," said retired agent Caroline Aguirre, who has made a second career of holding the department more accountable since she retired in late 2007. "This way you don't discover violations and you don't have to return them to custody."

Last year, Los Angeles police responding to a vandalism call at the Ramona Gardens housing project were fortunate to avoid being shot by a parolee under the medium supervision level, known as controlled service.

Oscar Velasquez was 20 when he went to prison for murder in 2002. Known as "Snake" in his Los Angeles gang, Velasquez was released in December 2008 and placed on controlled service, meaning he had to report to his parole agent once every two months.

When police confronted him for vandalizing the housing complex weeks after he was released from prison, he pulled a shotgun and began firing. As officers returned fire, he dropped the shotgun and ran.

As police closed in, Velasquez began shooting again and was arrested. He is awaiting trial on charges of attempting to murder a police officer.

Another parolee on infrequent supervision, Donald Austin, is now facing an attempted-murder charge in the Central Valley's Madera County.

Austin was a five-term prisoner whose history included guns, drug abuse, evading arrest and hit-and-run. But he was on controlled service after being paroled in September on a burglary conviction.

In March, Austin was suspected of trying to kill a man by driving into the victim's go-cart. The man was seriously injured; Austin got away.

He was sighted days later, but "the subject placed the car in reverse and drove full speed at the deputies," a parole briefing states. "The deputies fired their weapons at the vehicle and a short pursuit ensued before the vehicle crashed."

Austin was captured and jailed last month.

Despite a violent past that includes arrests for kidnapping, assault and robbery, Charles Samuel was placed in a sober-living home on minimum supervision after his release from prison in February 2009.

Last summer, after getting a day pass, Samuel beat 17-year-old Lily Burk to death. Police found him hours later, wandering Skid Row with a drink in his hand and blood on his clothes.

In a Los Angeles courtroom Friday, he admitted he killed Burk and was sent back to prison for life. This time, he will never be eligible for parole.

"They're being asked to manage an extraordinary number of people," Barry Krisberg, a distinguished senior fellow at the University of California Berkeley Boalt Hall School of Law, said of the corrections system. "People get released who shouldn't be released. Then you have people who should have been released but stay longer. The system can't even manage the basics.

"We have to do something different, and part of that means being much more selective in who we're going to invest tight supervision on and who we're going to allow back into the community."